Why, Why Now and So What…. The Big “P” in Municipal Policy

This article is part 1 of 7 in a series.

As part of work in municipal policy development, one of my noticing’s has been the discrepancy between what I refer to as: small “p” policy and big “P” policy.

By small “p” polices, I am referring to the operational municipal policies that establish rules and responsibilities to address requirements and protocols. These are helpful to guide municipal day-to-day operations. Examples might include sponsorship, expenses, rewards programs, investment, or remuneration polices.

When I consider big “P” policies, I am signifying a strategic framework that guides long-term decision making. These big “P” policies refer to public policies the municipality has enacted – generally speaking, the fundamental choice of the municipality to do something, or nothing, as it relates to their goals[1]. This level of policy sets the course for the organization on significant topics facing the municipality and helps to guide future efforts in a systemic and impactful manner. Examples might include climate change, affordable housing or recreational planning policies.

Based on these noticing’s, I am excited to have you join me in this journey to explore big “P” policy development in the municipal context.

The Policy Cycle

It is not uncommon to uncover that a program or project does not have public policy in place guiding the work. It can become uncertain where direction for the project was derived from, particularly for legacy projects. We can find ourselves pouring over past meeting minutes to identify policy direction or reviewing historical documents to better understand the path of an initiative. Due to the onerous nature of this investigation, it is not surprising to instead concentrate our efforts on reviewing, updating or developing tools, programs, and resources rather than focusing on the outcomes these implements were originally intended to address.

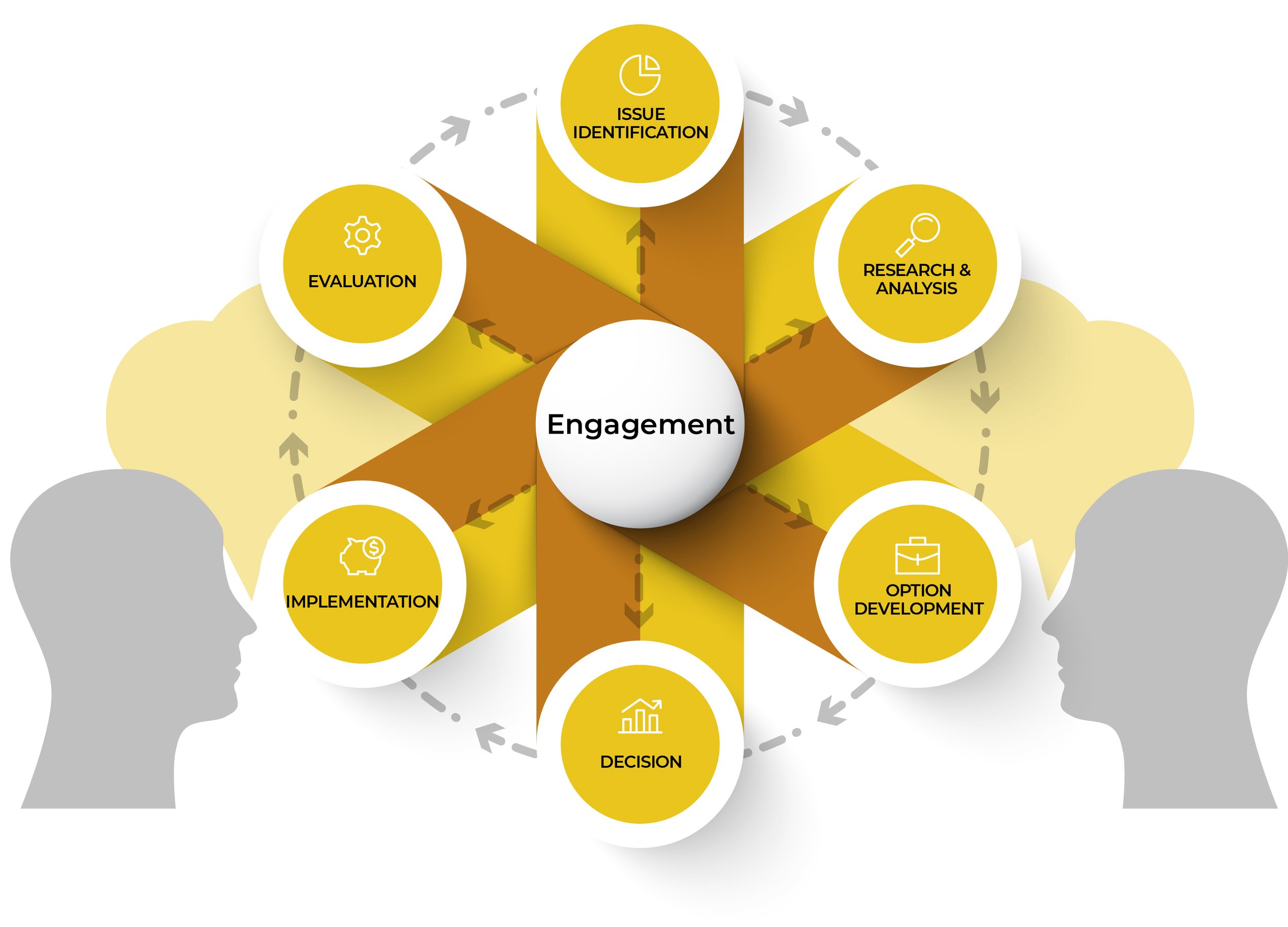

To avoid this enigma, applying the policy cycle can be an effective tool to develop public policy that strategically guide efforts.

The policy cycle is a pattern of stages that provides insights into the decision-making process, originally developed in the late 1950s by Harold Lasswell[2]. In our work with municipal clients to establish public policy, we apply the policy cycle, including overlaying how public engagement can support decision-making.

Issue Identification

While the policy cycle is circular in nature, typically developing public policy begins with Issue Identification and exploring three important questions:

Why: How often have you been in a meeting discussing an issue, only to ask yourself – why are we working on this? Unfortunately, too often this comes late in the process, and you may not want to raise it for fear of derailing a project already in motion. However, this is a critical question when addressing a significant topic. It can clarify why this issue is important to the municipality and what direction is needed to support long term goals.

In supporting municipal public policy development, we often practice the Five Why’s Technique, originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda, found of Toyota Industries, to determine the root cause of an issue to be solved[3] and to ensure we are focusing on the right problem.

Let’s practice using a recreation example many municipalities face, such as the need for soccer fields.

Starting Issue: The Municipality Needs More Soccer Fields

As we work through this technique, we realize that the issue is not necessarily that we need more soccer fields, but instead, we need to better understand user needs and the ability for the municipality to provide for those needs. This exploration may then lead the municipality to explore initial research and analysis to investigate this issue further. Based on this exploration, the issue may be reframed as the need to develop a 10-year Sports Field Strategy to set public policy and guide future decision-making rather than address a single issue.

Why Now: Once the issue is framed at its root, the next question is: Why address the issue at this time - why now, and not 6 months or 2 years from now? This examination applies a systems lens that considers contributing factors such as the budget cycle, Strategic Plan priorities or alignment with other major projects. It ensures the development of the policy is taking place at a time that makes connection points with other critical factors. It can identify whether a project needs to take place immediately or illuminate that more time is required to better understand the issue.

Let’s revisit our sports field analogy. Developing a 10-year Sports Field Strategy may need to occur at this time based on:

Increase in user needs over the past 5 years that have not been addressed

Alignment with the community health and wellness recommendations

Risk of increased future capital costs

Opportunity to work with regional partners and stakeholder groups

Alignment with priorities in the asset management plan

Opportunity to leverage available grant funding

So What: Lastly, we seek to ascertain the impact of the policy decision. If we undertake developing a policy to address an issue at this time, what outcomes do we hope to achieve and who will it impact? Again, using our sports field analogy, the impact of developing a 10-year Sports Field Strategy may:

Support future decision-making on community recreation investment

Identify implementation approaches

Strategically address multiple user needs

Foster relationships with user groups and partners

Reduce risk of future financial costs

Depending on the scope of the issue at hand, the issue identification phase may take substantial time and effort to clarify key considerations, including undertaking internal and external engagement. We will be exploring the role of engagement in an upcoming article. Regardless of the issue, properly framing it is key to providing clarity throughout the project, reducing scope creep, managing timeliness and budget, fostering open and transparent communication and bringing a collaborative mindset to the project.

The next step is undertaking research and analysis to further unpack the issue. This stage of the policy cycle will be explored in the next article.

If you are interested in learning more how the policy cycle can support your work, please contact:

Dana Garner Senior Consultant at Emerge Solutions, Inc.

dana@emergesolutions.ca

emergesolutions.ca

[1] Dye, Thomas R. Understanding Public Policy. 1972

[2] Savard Jean-Francoise. Policy Cycles. Retrieved October 12, 2022 from Encyclopedic Dictionary of Public Administration: https://dictionnaire.enap.ca/dictionnaire/docs/definitions/definitions_anglais/policy_cycles.pdf

[3] Van Vliet, V. (2014). Sakichi Toyoda. Retrieved October 12, 2022 from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/toolsheroes/sakichi-toyoda/